Disclaimer:

Please be aware that the content herein has not been peer reviewed. It consists of personal reflections, insights, and learnings of the contributor(s). It may not be exhaustive, nor does it aim to be authoritative knowledge.

Learnings on your challenge

What are the top 5 key insights you generated about your frontier challenge during this Action Learning Plan?

Insight 1: Navigating the microworlds of Tonosí using collective intelligence.

We learned that conducting three smaller focus groups in communities and in-depth interviews with recyclers contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the different SWM dynamics before the collective intelligence workshop at the town center. The participants of these focus groups chose one person to represent them, which helped articulating their voices and perspectives during the collective intelligence exercise.

Some key findings were that waste is managed in a myriad of ways:

-In the upper valley, there is no public or private waste collection service, in consequence, burning is and burying is the common practice.

-In coastal areas, there is no municipal waste collection service, but there are private ones. All of them operate independently from the municipality and local governments, except for one that is paid for by the local community government to provide this (public) service as a private entity.

-In one particular case, the local community government bought their own waste truck and provides the waste collection service twice a month.

-At the town center of Tonosí, the biggest populated area of the district, there is a continuous waste collection service provided 2-3 times a week by the municipality.

The collective intelligence workshop showed us that, in systems practice, creating a common language is key. Some participants used words such as reduce, reuse, and recycle (the 3Rs). However, for others, especially from communities outside the center, their ways of describing alternative SWM practices were different. For example: many participants did not know what compost was, for them, a more familiar word was organic fertilizer. Similarly, when interviewing households and local businesses, there were many questions about what reduce, reuse and recycling mean, actually. Some of these were: “if I throw banana peels below my mango tree and the soil ‘eats the peel’, does mean I am doing composting? another citizen asked “is separating recyclable materials the same as recycling?” and what is the difference between reusing and recycling? As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry said: “language is the source of misunderstandings”. However, in this case, it became a starting point to generate a system’s understanding of SWM in Tonosí. One must be mindful at all times of power relations and how those define what constitute 'valid' knowledge when informing decisions on SWM

Insight 2: Recyclers, the most relevant example of effective recycling.

Only 7 recyclers have been identified in Tonosí, yet their contributions to SWM and the value chain of recyclables in the region is evident. They are the most relevant example of effective recycling in the municipality. We learned that the main materials recycled were ferrous materials such as iron, cupper, bronze and aluminum. For recyclers, recycling has a metal face. On the other hand, recycling of materials such as plastics, paper or glass was almost non-existent and they were not recovered by recyclers because there is no market for it in Tonosí. We say (almost) non-existent because we found that there have been several attempts to recycle these materials by community-based organizations in Tonosí with very little success. The main barriers mentioned were: (i) high logistics costs; (ii) price of recovered materials -mainly plastic, paper and aluminium cans- and (iii) lack of a recovery center and the understanding on how to prepare the materials to get the best value from it.

Insight 3: What is 'waste' made of and where does it come from?

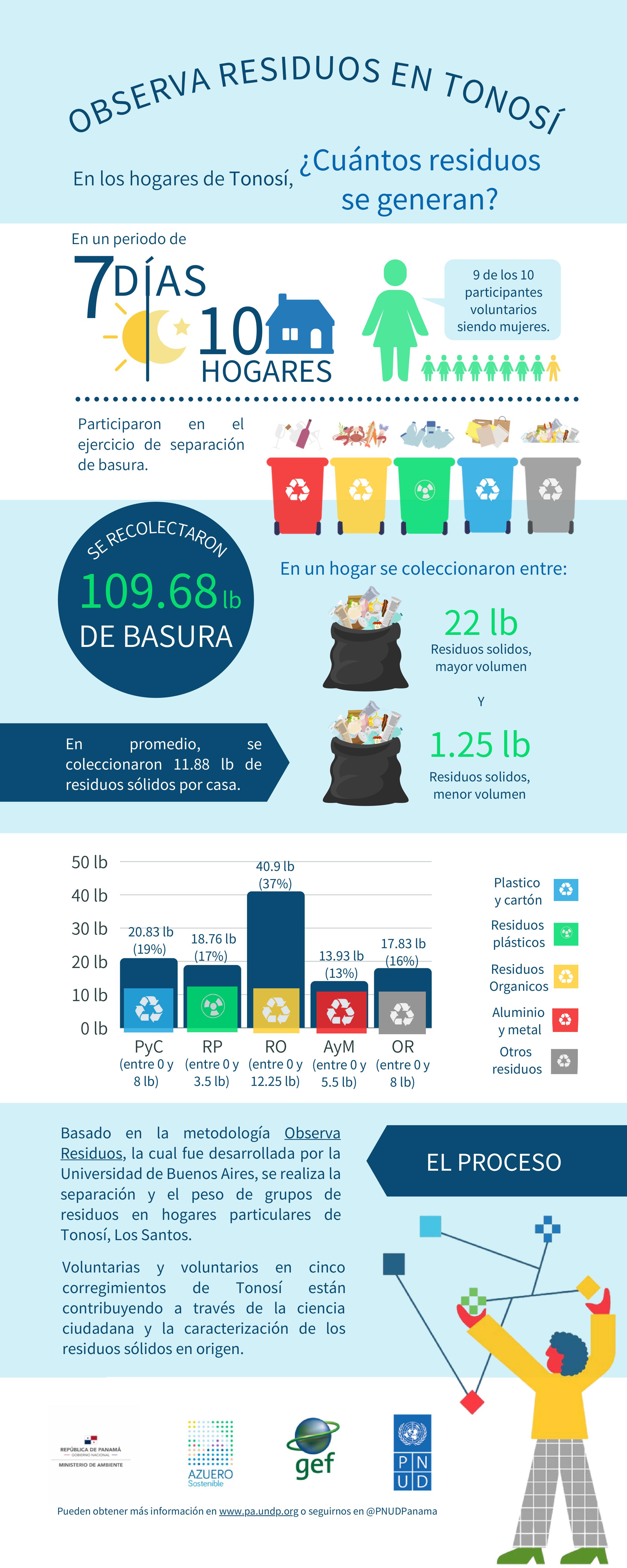

As part of a SWM diagnosis for Tonosí, conducted by a consulting firm, we found that similar to national, regional and global trends, the characterization showed that organic waste is the main type of waste found in landfills, representing 40% of all waste generated. Moreover, within that 40%; 40% of all the organic waste came from pruning-related activities. On the other hand, plastics (16%) and paper (8%) had the second and third highest scores. Comparatively, we conducted a brief exercise where we used a citizen science method developed by the University of Buenos Aires to identify the composition of solid waste in ten homes. For that, each household was given five differently colored bags as well as a set of instructions on how to separate their household waste in these five bags for seven days. At the end of the seven days, individuals weighed each bag and reported the weight of each bag to the Lab by sending in a photo of the bag being weighed (showing the scale). From that, we learned: The average Panamanian person produces 1.3 kg of solid waste each day (IaDB, 2020), of which 12% represent plastic in the waste stream. In Tonosí, the average household produces only 0.76 kg of solid waste per day, but 16%-17% of this waste is plastics. There are differences in the composition of household waste when applying the Quartering Method (a validated method that segregates household waste upon being recollected) and the Citizen Science Method (a new method that has individuals measure their own waste. The biggest difference can be found in organic waste (8% difference). The second-biggest difference can be found in aluminum and metal (5%). One explanation for this difference might be the small sample size used in the Citizen Science Method (N=10). The difference between the organic waste groups could be explained by individual household practices: Three out of the ten households in the citizen science project submitted zero organic waste. Upon inquiring about this, participants mentioned that they feed food scrap and other organic waste to their pets, farm animals, or use it as a rudimentary form of compost. Through surveying Tonosí’s households in three districts, we were able to confirm that, indeed, 35% of households apply composting (N=54) in their homes. Outside of the households, coastal communities such as Búcaro, Guánico and Cambutal continously mentioned that touristic activities leave large amount of waste on their beaches, especially plastics. This sparked curiosity about the extent to which plastics affect coastal-marine ecosystems and how citizens and businesses could take action to understand, prevent and find alternatives to plastic waste in their communities. In addition, plastics were a key concern identified through initial interviews with experts, key (local) social and institutional actors, and focus groups in communities. This interest me us decide to explore and experiment on this problem domain.

Insight 4: Citizen science - marine Litter and microplastics.

To identify the composition, source, and volume of marine litter and microplastics, and to validate the citizen science methodology, the Lab adapted the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s citizen science methodology and complemented traditional data collection by using of a mobile data collection app. This experiment was conducted with 16 participants in three different municipalities, Pedasí, Pocrí, and Tonosí, over a period of three days. Plastics represents between 68% (Tonosí) and 91% (Pedasí) of all marine litter found across the three beaches. This is a significant percentage, seeing as how the diagnostic demonstrated that plastic makes up only 16.19% of commercial as well as 16% of household waste. We also know that, at least in Tonosí, there is currently no circularity for plastic products (meaning no plastic products are currently being accepted by recyclers). These numbers show a serious plastic waste leakage problem in the solid waste cycle of the three districts and requires an immediate response to what appears to be a marine plastic crisis in the Azuero coastal region. Pocrí’s La Yeguada, a beach which is used both for tourism and for boats to dock, is the most contaminated of all beaches. However, the most contaminated shoreline (beyond the sandy or gravelly area of the beach) was found to be on Tonosí’s Guánico beach, a beach which covers a protected area for over 2,500 marine turtles as hatching grounds.

Insight 5: exploring Reverse Logistics with Coca Cola.

In an effort to develop a value chain for small municipalities that face logistics challenges due to distances, the Lab is seeking a partnership with Coca Cola to explore a reverse logistics model as an alternative to traditional linear economy models. During interviews of businesses and residents, we could not identify recycling any other material, especially plastic. It turns out that distance is a problem: distances are far, and population density is low (there are only about 7 people per square kilometer vs 116 in Panama City) the cost of transporting materials is too expensive for residents and not economically viable for recycling companies. Coca Cola was interested in hearing how the Lab was addressing plastics systematically, but they immediately identified potential roadblocks with our proposal: (i) The Ministry of Health does not allow for the combining of food items with waste items, (ii) In order to transport recycled material externally, Coca Cola would have to embark on a lengthy process of approving adaptations to their trucks, which would have to be reinspected and authorized to transit Panama’s roads safely. (iii) Coca Cola is skeptical of the volume communities like Tonosi could generate, stating that “Tonosi is just too small” as a community. Designing a proposal that would fit the needs of private actors – where they currently are, meeting them where it matters according to their bottom line -

Please paste the link(s) to the blog(s) that articulate the learnings on your frontier challenge.

Did you experience any barriers or bottlenecks when impacting the system, working on your frontier challenge respectively?

Citizen science: marine litter and microplastics Due to a spike in COVID-19 cases, region-wide mobility restrictions translated into a reduction in the number of participants. For three beaches, 36 participants should have been recruited. This number needed to be reduced to 16 participants. Citizen Science in households “Observe:Waste” This was a rapid test of the methodology and applied in a diverse territory, from coastal to upper valley communities. There was a short window of time to train and test and due to challenges coordinating the availability of the selected participants, different participants started separating their waste at different days. Given that we could not stay for more than one week in Tonosí, we had to continue the communication via cellphone and cellphone signal in Tonosi can be a challenge, particularly for more remote communities. Furthermore, halfway through the implementation the municipality was hit by a bout of COVID-cases, complicating logistical aspects of the municipality’s involvement. Diagnosis on the situation of SWM in Tonosí: The diagnostic was conducted within an abbreviated period and there were many coordination challenges within the consulting firm and key local actors. This resulted in an insufficient number of interviews to consider it a representative sample, which still leaves an information gap in this process. Municipal Plan for SWM: As part of the consultancy, the last product is to present a Municipal SWM plan. Regardless, the consulting firm has struggled to articulate our Labs interventions with the proposed plan. We are currently reviewing and working together with them to integrate our interventions under this plan to the extent possible. Missing links in the system: Recyclers: when engaging with recyclers in Tonosí, we missed to connect them to the National Movement of Informal Recyclers due to long distance and related costs. There is a chance that this articulation happens as part of the reversed logistics pilot, but it is not clear at this point. Pilot Project with Coca Cola Coca Cola showed reluctance in developing a pilot project due to the distance of Tonosi from major metropolitan areas as well as projected low volume of plastics. Original ideas proposed for the Lab were met with skepticism and explained as initiatives that had been previously thought of, albeit not implemented. The Lab had to conduct the diagnostic to have relevant data to sustain a proposal that Coca Cola would be interested in supporting.

For this frontier challenge, how much of your time did you dedicate to the stages in the learning cycle? Please make sure that your answers adds up to 100%.

Data and Methods

Relating to your types of data, why did you chose these? What gaps in available data were these addressing?

Citizen-generated data and participatory observation were used to validate citizen science as a data collection and analysis method in the SWM field. While we were able to conduct a complete SWM diagnostic with the support of several actors in one municipality, many municipalities or townships won’t have the resources to conduct this process. Citizen Science manages to address the gaps through collective action in the communities while providing citizens experiential learning and empowering to participate in environmental management. Geospatial data was used both to map out the solid waste recollection routes as well as to map the distribution of marine litter (through a mobile phone application) Expert interviews were used to ensure that the data generated through the citizen science (marine waste & microplastics) would fill a relevant gap in the existing literature around marine waste and microplastics in Panama. For this, we spoke with experts from the University of Chile, UN Environmental Program, Panama’s former minister of environment and current staff of the national Marino-Coastal Department, University of Georgia, Florida State University, and others. Literature review (policy review) was conducted to create a theory of change for the citizen science (marine debris / microplastics) intervention based on the RBM framework. Scientific research is currently being used for an in-depth analysis of the macro- and microplastics found. Results of this are still being processed and will be shared in the form of an academic journal publication. In addition, when exploring the contributions of recyclers to SWM in Tonosí, we came across the National movement of Recyclers (MNRP), which in turn connected us with academics from the University of Panamá (UP) that have been supporting them in their efforts to protect the rights of recyclers; as well as generating evidence on their current situation and the need to include them in SWM programs, projects, and plans. Based on research conducted by University of Panama scholars (Farnum & Kelly, 2018), we learned that recyclers were part of the development of research instruments (surveys). This same instrument was used to understand the situation of recyclers in Tonosí with the guidance and support of the National Movement of Recyclers and UP scholars. In-depth interviews were conducted as part of the ethnographic effort to better understand the daily life, aspirations, and challenges of recyclers in Tonosí. Recyclers generated data through quartering: as mentioned before, recyclers supported the characterization of waste from households and businesses at the municipal landfill. This process was done using the method of ‘quartering’, which consists in separating the waste from the waste truck in four, smaller, heterogeneous samples (Rojas-Valencia et al, 2012). Followed by choosing two to conduct the characterization of waste. This was helpful in addressing the lack of data with regards to waste generation in quantity and composition in Tonosí and the Southern region of Azuero.

Partners

If applicable, what civil society organisations did you actually work with and what did you do with them?

The National Movement of Recyclers has been key in guiding our learning process. They are part of our ‘coordination team’ that meets periodically to discuss on progress and learnings from this process. We have collaborated in the application of the quartering methodology for waste characterization and the use of the survey instrument elaborated by them and Farnum & Kelly (2018) in Tonosí. There may be an academic publication generated by the University of Panama.

If applicable, what academic partners (and related institutions) did you actually work with and what did you do with them?

The University of Buenos Aires: Developed and applied the citizen science method Observe:Waste in Argentina. Upon its adaptation and application in Panama, the developers of the methodology facilitated further guidance of the methodology and its dissemination. Florida State University Supported the design of the Theory of Change and concept note of the citizen science (marine debris and microplastics) methodology. The Technological University of Panama The Center of Hydraulic and Hydromechanics designed the field method used for citizen science (marine debris and microplastics), trained the citizen scientists in the fields of plastics, data collection, data analysis, and legal and regulatory frameworks for plastic. This partner is currently also leading the in-depth analysis of microplastics and is supporting the scaling of the method to Guatemala and El Salvador. We partnered with the Regional Center of the Technological University of Panama in Azuero to explore alternative solutions to SWM in the southern region of Azuero through the Innovation Fair titled “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle and Be an Entrepreneur”. Given that most eyes look at Panama City when searching for innovation and entrepreneurship, this became an opportunity to explore and showcase innovative solutions emerging from university students of Azuero. In total, there were 24 proposals and the top 3 selected were (i) artificial reefs; (ii) app to find recycling companies in Azuero and (iii) yucca ‘plastic’ in replacement to polystyrene. University of Panama Raúl Kelly, scholar from the University of Panamá has continously supported our learning process participating actively in the ‘coordination team’ meetings. We have collaborated in the validation and application of the quartering methodology for waste characterization and the use of the survey instrument elaborated by him in Tonosí (Farnum & Kelly, 2018) together with the National Movement of Recyclers.

If applicable, what private sector partners did you actually work with and what did you do with them?

Coca-Cola: ideation of reverse logistics pilot in Tonosí After noticing Coca Cola’s presence in Tonosi as a steady distributor, while considering that most residents and businesses are not recycling plastic, the Lab pitched a reverse logistics proposal inspired by Coca Cola’s vision of working towards a ‘World Without Waste’ – aiming to collect and recycle a bottle for everyone sold by 2030. The proposal, currently under evaluation, encompasses four key elements: Phase 1: educate participants on waste separation and collect data on the amount of material collected Phase 2: with the municipality to compact the collected material in the center of Tonosi Phase 3: evaluate the financial sustainability of the pilot through a relationship with a local recycling company, Recimetal Phase 4: evaluate the effectiveness of the model and explore options to incorporate the collection process into Coca Cola’s logistics chain. Recimetal: partner for reverse logistics pilot Recimetal is one of Panama’s largest recycling companies that has advised the Lab regarding the logistics of recyclable materials in Panama as well as committing to training in plastic compacting as well as retrieval and payment of materials.

End

Bonus question: How did the interplay of innovation methods, new forms of data and unusual partners enabled you to learn & generate insights, that otherwise you would have not been able to achieve?

Please upload any further supporting evidence / documents / data you have produced on your frontier challenge that showcase your learnings.

3Good health and well-being

3Good health and well-being 12Responsible consumption and production

12Responsible consumption and production 13Climate action

13Climate action

Comments

Log in to add a comment or reply.